Here’s the Weekly Writers Monday post. Thanks to my paid subscribers, today’s post is open to everyone.

Public Lending Right (PLR)

In some countries there is a PLR (Public Lending Right) system which is set up to make payments when registered authors’ books are loaned from libraries. In the UK the PLR system is administered by the British Library and you can register any title you’ve written which has an ISBN, in return for (possibly) getting payments if the book is borrowed in significant numbers from public libraries. In 2024 the rate paid for each loan of a registered work was 13.69 pence per loan.

Personally, I think PLR is a waste of time. Let me count the ways.

1. Unnecessary Admin For Little Gain

PLR requires an annual pot of money from public funds (£6.2 million in 2024; costs for staffing and administering the system are on top of that), significant infrastructure, and administrative work for every author in the country.

As we saw in previous posts, there is a highly unequal distribution of income in our business, and PLR is no different. It is structured to favour the authors who already sell a huge amount of books. Those big-name authors with lots of sales get the maximum payment (£6,600 in 2024) and bulk of the money from the PLR pot, while lesser-known authors (who desperately need the money) usually get little or nothing. For them, the time applying, and keeping their account up to date, may cost far more than any money ever made from PLR. Do JK Rowling, Lee Child and James Patterson need the extra money? Patterson spent thirteen consecutive years at the top of the list with the maximum payout, yet his total income over a decade is estimated at $700 million.

Interestingly, the maximum amount awarded (£6,600) has barely increased in 20 years. It was £6,000 in 2001, which would, in today’s terms, equate to c. £12,000 if it had kept up with inflation. The value of PLR had basically halved in that time.

And it is a lot of bureaucracy and work for authors. Every author has to manually set up an account, maintain it, update it, correct errors and so on. Also, BL staff are paid to administer the system, to set up software and databases and security, with the reporting another burden on libraries. The interfaces are, in my opinion, clunky and frustrating to the point that I dread having to do anything with PLR. And all paid for by public money. A significant amount is funding intermediaries rather than going straight to authors.

2. PLR Is Discriminatory

We have bolted-on systems, and cobbled-together laws for a single profession (authors) within a single industry (creatives). What about other industries where people struggle? What about other creatives such as musicians, artists, sculptors, dancers?

And, while questioning things: why does PLR apply only to borrowed items? Most libraries have reference collections which cannot be borrowed, but readers make the same multiple use of reference works as they do of the loan stock.

Why does PLR apply only to books? Many other media are stocked and can be used in, or loaned from, libraries.

Why is PLR confined to public libraries? Books are loaned from all kinds of libraries, including school and academic libraries; currently many authors (of textbooks and non-fiction) won’t ever be remunerated.

Why does the scheme reward the most popular authors, rather than aiding authors who most need the financial support?

The whole kit-bashed system is neither efficient, elegant, not practical. Piecemeal laws conjured up for just one small group are short sighted. Instead we should create systems that benefit everyone, not just those that shouted the loudest.

3. The World Of Libraries Has Changed

When the UK PLR scheme was implemented in 1982 (Public Lending Right Act) the world was different. There were far fewer authors, and far more libraries. In fact, library services and budgets were growing. It doesn’t surprise me that some authors wanted a piece of that pie. It must have seemed like libraries would go from strength to strength, and account for more and more book sharing.

How naive that was.

Libraries are closing, and their services are cut at a depressing rate. Councils see them as low priority, soft targets for budget cuts. Many libraries have a freeze on acquisitions, meaning they can’t even buy any new books. We are also seeing increased calls from the private sector to do away with libraries and replace them with … the private sector. If this continues then PLR will be for nothing, because there won’t be libraries left to loan books. When the existence of libraries is threatened, it seems churlish to be bothered about whether our books are being read more than once by library patrons.

I also think the view of libraries has changed. Back in the 1970s many authors believed their publishers, who claimed book lending (and resales) were a “threat”. PLR was seen as a counter to that.

Many trade publishers have never updated their old-fashioned views. They equate libraries sharing books with lost sales. Publishers try to wring every penny from libraries, even charging them more for books – up to ten times the retail cost – and placing restrictions on ebooks.

Except … it wasn’t a threat.

I don’t start from the negative view of libraries as somehow stealing bits of our livelihoods (the HMRC do much more of that), but view libraries as vital partners where we should be only too glad to have them buy and share our books. Libraries are great! I’d worked in public and academic libraries ever since I left school. Here are some counters to the out-dated view of libraries held by some publishers.

Many of the people using libraries couldn’t afford to buy the books they read. If the books weren’t in the library, there would be even fewer sales, and also fewer fans. You tend to find that people with money prefer to buy books, and those without borrow them, as with many other items.

Many of us authors first fell in love with words and stories thanks to borrowing books from libraries.

Libraries make a huge contribution to the economy, education, well-being and literacy, despite falling Government expenditure. They’re a social service. To take this further, the thing that threatens author income isn’t piracy, or libraries, it is obscurity. The more people sharing our books and talking about them and getting a taste of our work, the better. Actually, let me add: the other threat is people not reading. People choosing to watch TV or play games rather than read books. Libraries are one of the champions trying to turn that around and encourage literacy.

Nowadays “library pricing” means libraries already pay a higher price than you or I would when they buy books (and hopefully a fair proportion of that increase goes back to the author). PLR has been superseded.

Every book sold to a library is still another book sold! According to the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) there are 2.8 million libraries worldwide. If even a fraction of them bought a single copy of my books, I’d be rich. Sales to libraries internationally can be a significant boost to the income of authors, without needing a piddling extra drib of PLR money that may not even buy a pint of beer a year. (If you aren’t already a public library user, then join one – it is free, and provides you with a wealth of education and entertainment.)

It’s worth mentioning that IFLA opposes PLR, and has stated that the principles of “lending right” can jeopardize free access to public libraries, which is a far more important human right. This is also why many authors oppose PLR, including Nobel Laureates José Saramago and Dario Fo.

Reusing books is good: if we care about the environment (which I’ll discuss in a future post for paid subscribers), shared library copies are a great way to mitigate the harmful impacts of book production.

Libraries are friends to authors. Since libraries have so many book-loving customers, placing your book in a library is like they are paying to promote your work for you! It can be a vital element of exposure to readers. Voracious book lovers may well go on to buy their own copies, and stock up on your other titles, as well as leaving reviews for your work. Win win.

The times have changed, and PLR is a bureaucratic relic whose time has been and gone. Do away with it, and all the admin, and give the money to struggling libraries instead. That would benefit authors (and everyone else in society) far more than PLR.

4. Issues With The British Library Itself

The British Library took over the UK’s PLR system in 2013. I have a background in customer support, software, libraries, and technology, and one of my skills is in analysing systems and processes from a user perspective. I’ve been in touch with the British Library’s PLR staff many times over the years, flagging up issues with their systems or processes, user interface and platform, and making helpful suggestions for improvements. I was even interviewed by Softwire consultancy, who the British Library commissioned for their PLR user research project. The point is, I gave up a lot of my time in order to try and help them, and improve things for everyone using the systems.

Unfortunately, instead of fixing issues or (eventually) implementing improvements and thanking me, I always got the impression that the senior staff weren’t interested, and most of the issues I raised were still the same years later. I remember discussing improvements with their Author Operations Manager, and also the Head of PLR Operations: both told me their new system would include improvements. When the new system eventually launched in 2021 I discovered five useful features of the old system were removed, and my suggestions for improvements not implemented: I ended up with something I found to be inferior in many ways to the 12-year-old system they replaced.

What kind of issues am I talking about? Clunky interfaces; things not working as well as they should; bugs; strange design decisions; a lack of useful features such as a data notes field; hidden options; inconsistent data titles; downloads that missed out data; “security” which meant I couldn’t easily access my own data for over a month; delays in registering books or making changes; and many more. Sometimes their staff didn’t understand their own internal systems and gave incorrect information; in one case I solved the problem myself, and explained to them how their buggy input form (which hadn’t been programmed to deal with curly apostrophes) led to false positive error reports. Thanks to me identifying this, they were finally able to fix that issue.

Time for a small revelation. I almost certainly fall somewhere on the autistic spectrum. During my life I’ve gradually come to realise that my continuous inner dialogues, hyper sensitivity, recurring depression, light-related moods, swings between exuberance and being withdrawn, a thought mechanism combining fundamental logic with extreme empathetic faith, conceptual obsessions, and repetitive thought patterns (amongst other things!) aren’t the same as the subjective experience of many other people. It’s why I can talk for hours on a topic that interests me, but have trouble with small talk and formal conversation. It’s similar to a situation in my childhood: I was short-sighted, but didn’t know it. I assumed the world was blurry for everyone, and it was standard to examine the blackboard up close after a class to see what the teacher had written on it. Then one day I had an eye test, was pronounced myopic, given a pair of black NHS spectacles, and realised the world looked totally different. For the first time I understood how people knew which shop to go in: they weren’t relying on vague colours, sounds and memory, but could read the writing above every shop! It was a paradigm-shifting “A-ha!” moment. Likewise when I read about the thought processes of neurodivergent people a few months ago and realised they matched mine, and they were different from how most people experienced things: a-ha! It explained so much. And, just as I don’t see my depression as being an illness that needs fixing, but a natural response of a compassionate mind to all the injustice and cruelty we see in the world, so the realisation of my particular mental makeup just showed how different we all are. My friends and loved ones had long suspected that I was “somewhere on the spectrum” as they told me. They put up with me anyway because they also know that compassion, questioning everything, and an obsession with improving things aren’t bad traits. But strangers can be forgiven for misconstruing my persistence and assertiveness when I believe something could be easily fixed or improved. In my mind I am trying to benefit everyone, but strangers may see my analyses as interference. I suspect that’s what happened with some staff at the British Library in 2021.

They’d done their best to brush me off, and I got the feeling they just weren’t motivated to improve the system. (That feeling of mine may not have been accurate, but all I had to go on was their responses and the many issues that hadn’t been improved when there was the opportunity, such as their software upgrade.) In November 2021 I did an FOI request to the British Library about the issues I’d raised and their responses … well, it was revealing.

For example, I’m involved in various author communities where we share information and experiences, and support each other in our work. It’s one of the things I love about authors! And I had listed some of the issues with the British Library PLR systems, which led to valuable discussion about what authors really need. As part of it I quoted some British Library emails I’d received.

The FOI request revealed the British Library had considered legal action against me (using public funds) as a result, and their complaints to Twitter got my account blocked. Luckily Twitter quickly removed the block and acknowledged I hadn’t broken any rules, but the British Library senior staff’s behaviour here seemed rather spiteful to me. I hadn’t realised how much the British Library hates criticism!

After my negative experiences with them I wasn’t surprised to hear that the British Library’s security was inadequate and they were hacked in October 2023, with data stolen and their systems compromised (and it took them a month to email users about this, advising us to take precautions … a bit late, methinks). If we hadn’t had a PLR system run by the British Library, then there would be no PLR author data to steal in the first place.

“But if you dumped PLR, wouldn’t we be worse off?”

Setting up piecemeal interventions for each industry is costly, complicated, and unfair. I’m more interested in systems that help authors with low incomes, but also help everyone on low incomes.

It’s why I’ve always been very interested in the growing movement for a Universal Basic Income (UBI), as has been championed by the Green Party for over a decade. The idea of UBI is that it’s paid to all, free of increasingly-harsh sanctions and conditionality. As a result it provides an income safety net which vastly reduces poverty, whilst freeing people up from financial struggles, precarious employment and social exclusion so that they have more options to take part in whatever they want: study and education, extra paid work, creative endeavours (hello authors!), democracy and community, being a carer, voluntary work and so on. If you lose your job or have a difficult month you don’t have to go through the time-consuming and potentially stigmatising process of claiming benefits: you’re already being paid. And because you already were, you will also have been better off financially, and more likely to have been able to put aside savings. You are less at the mercy of forces imposed upon you. Disparities in income would be lessened.

So, specifically in terms of authors: it would provide a guaranteed income so we could afford to write. With UBI, authors would be better off than they would have been with PLR, but so would everyone else in the UK. And this system treats everyone equally, in every industry, every creative profession. With political will from all the parties this is achievable.

Consider this topic the next time politicians clamour for your vote. The billions spent by the UK and US on invading other countries, maiming and killing their inhabitants, and supporting genocidal regimes, would be much better spent making life better for us.

Thanks for your support!

Karl

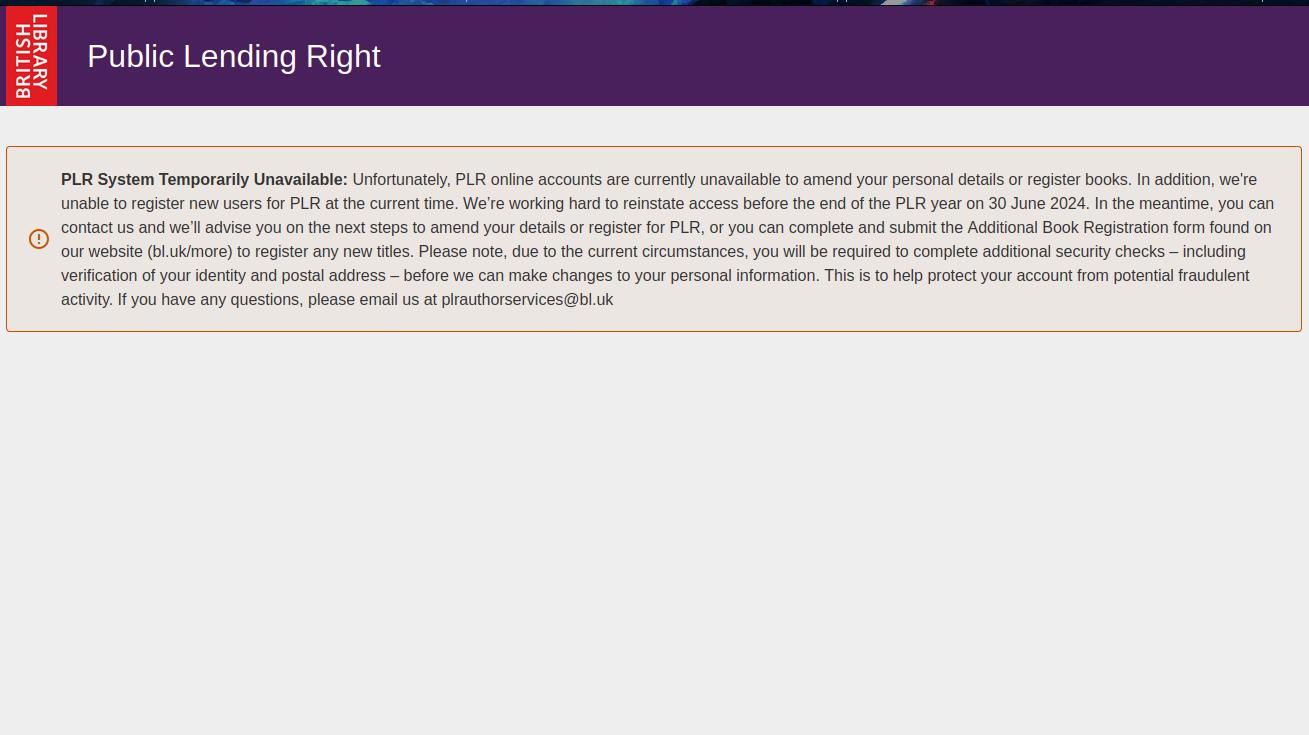

Update 2024-06-11

The British Library were hacked in October 2023. It’s now June 2024 and it still isn’t possible to upload or edit data about my books. Honestly, they seem like a bunch of incompetents. Screenshot taken just now: